I. The Sound of Scissors in Tokyo

The story doesn’t begin on a runway.

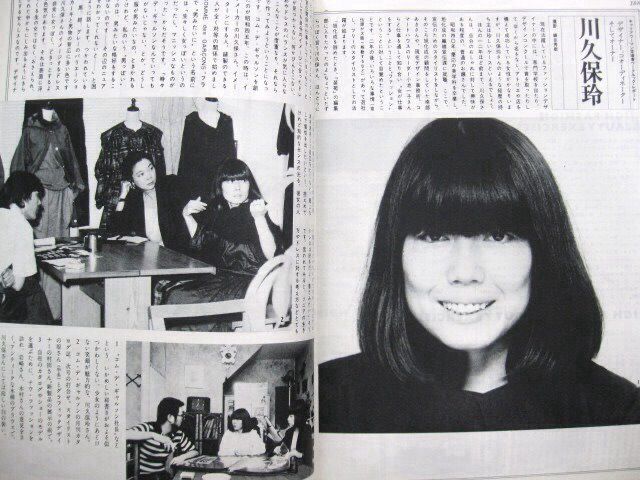

It begins with the sound of scissors — snip, snip — slicing through black fabric in a tiny Tokyo studio in 1969.

There is no perfume of luxury here. Only the smell of cotton, the hum of a sewing machine, and the quiet defiance of a woman who does not believe in beauty.

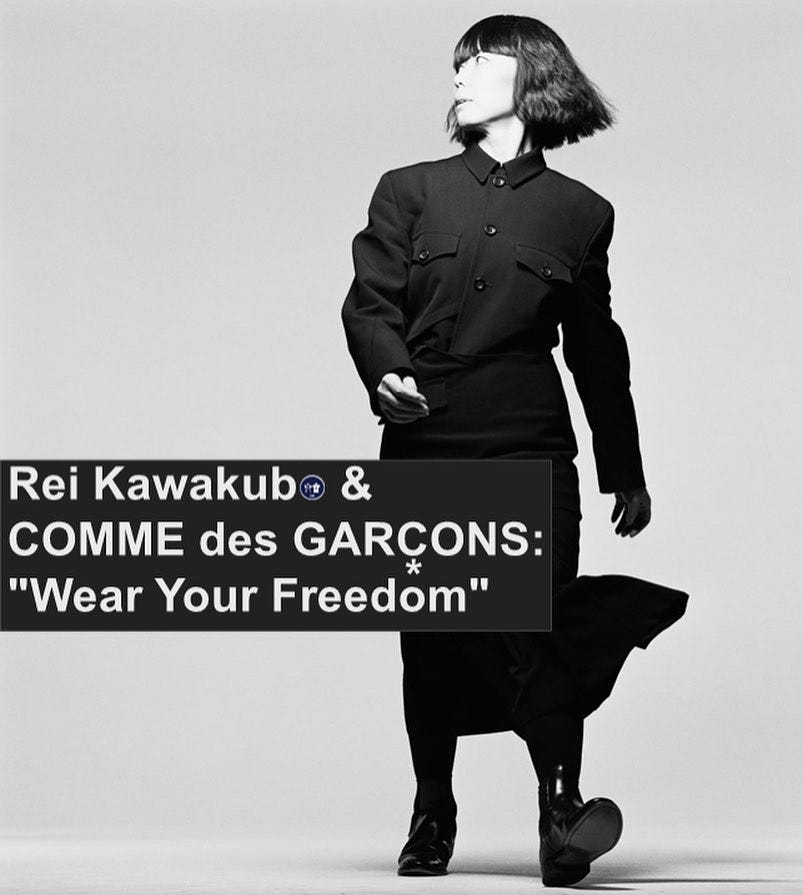

Her name is Rei Kawakubo.

Her language is clothing.

Her weapon is silence.

“For something to be beautiful, it doesn’t have to be pretty,” she once said — and that single sentence would tear through the glossy skin of fashion’s world like a razor through silk.

In a post-war Japan obsessed with renewal and refinement, Kawakubo began to build her empire of imperfection. Her label — Comme des Garçons — bore a French name that meant “like boys.” It was her first act of rebellion, a whisper that gender could be rewritten, that fashion could be more than costume — that it could be philosophy.

II. The Black Sun Rises

The 1970s Tokyo streets were a parade of conformity.

Women in immaculate suits, men in uniform precision — all chasing the promise of Western modernity.

But in the shadows of Shibuya and Harajuku, something darker flickered.

It was the black sun of Comme des Garçons.

Kawakubo’s early collections were not clothes to be worn. They were armor.

Dresses like questions. Coats that refused to flatter. Shapes that fought the human body.

They were stitched in monochrome silence, speaking a new aesthetic language — wabi-sabi translated into wool. The beauty of decay. The poetry of the undone.

╭──────────────────────────────╮

│ “I work in the space between │

│ the old and the new.” │

│ — Rei Kawakubo │

╰──────────────────────────────╯

By 1973, Comme des Garçons Co., Ltd. was official.

By 1975, she had launched a menswear line — Comme des Garçons Homme.

And by the end of the decade, Japan’s youth had found its quiet revolution: a black uniform for those who refused to fit.

III. The Crossing — 1981, Paris

Imagine the lights dimming at Paris Fashion Week, 1981.

The air thick with expectation. Then — silence.

And from the darkness, they emerge.

Models dressed in shredded black.

Garments frayed, asymmetrical, distorted.

The body — reshaped, questioned, defied.

Critics called it “Hiroshima chic.”

Some gasped. Some laughed.

But history would remember it as the moment fashion learned how to feel.

Kawakubo didn’t speak French. She didn’t need to.

Her designs were her dialect — a translation of thought into thread.

The West, with all its heritage of couture and perfection, had just been challenged by a woman who believed in ruin as creation.

“The only way to make something new,” she would later say, “is to stop caring what people think.”

IV. The 1980s — A Symphony of Imperfection

The decade that followed was less an evolution than an explosion.

Comme des Garçons became the philosophy of deconstruction — the art of tearing things apart to see what truth might remain.

1982 — Destroy

Clothes with holes, seams left visible, fabrics burned. The beauty of chaos.

1983 — Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body

Padded, lumpy silhouettes distorted the figure — fashion critics saw madness; artists saw liberation.

1986 — Homme Plus

Menswear turned inside out. Tailoring inverted. A rebellion in stitches.

Every show was a poem made of cotton and courage — each collection a confrontation between the body and the mind.

The color black became her anthem. It was not mourning — it was freedom.

V. Perfume of Smoke, Scent of Thought — 1990s

By the 1990s, Comme des Garçons had transformed from an underground whisper to a global dialogue.

But Kawakubo did not chase the world — the world came to her.

She built an empire of sub-labels — each a universe:

| Label | Year | Essence |

|---|---|---|

| Comme des Garçons Parfum | 1992 | Smoke, tar, spice — scents that refuse gender |

| Junya Watanabe CDG | 1994 | Futurism, technology, rebellion |

| Homme Deux | 1996 | Tailored austerity |

| Tricot CDG | 1999 | Texture and warmth through knitwear |

Her first perfume smelled not of flowers but of fire.

It was a statement — that even fragrance could think.

“You can’t make something new without breaking something old,” she said.

And in that decade, she broke almost everything — and rebuilt it better.

VI. The Heart Has Eyes — 2000s

The new millennium brought a softer rebellion.

In 2002, a small red heart with two eyes peeked from a t-shirt.

Comme des Garçons PLAY — simple, lighthearted, instantly iconic.

Designed by Polish artist Filip Pagowski, the logo became the heartbeat of a new generation: approachable, ironic, pure.

But while PLAY became global pop, Rei Kawakubo was busy reshaping reality.

Dover Street Market — London, 2004

A department store? No. A temple.

Kawakubo called it “beautiful chaos.”

Each brand — from Gucci to Supreme — was curated as an art installation.

It wasn’t retail; it was ritual.

Collaborations That Changed the Game

- Nike x Comme des Garçons — movement as concept

- Converse x CDG PLAY — streetwear as canvas

- H&M x CDG (2008) — avant-garde meets accessibility

- Louis Vuitton x CDG — heritage meets rebellion

Through it all, Kawakubo proved that commerce and concept could coexist — if one led with soul.

VII. The 2010s — Fashion as Sculpture, Art as Language

By the 2010s, Rei Kawakubo was not making clothes anymore.

She was building worlds.

White Drama (2012) —

A meditation on life’s ceremonies: birth, marriage, death — all in white.

Not Making Clothes (2014) —

A manifesto. Shapes without function. Clothing without compromise.

The Met Exhibition (2017) —

“The Art of the In-Between” —

Only the second living designer ever honored at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Her creations stood silent in glass, like relics of the future.

╔═══════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ “I make clothes for women who are not swayed ║

║ by what their husbands think.” ║

║ — Rei Kawakubo ║

╚═══════════════════════════════════════════════╝

In that decade, Comme des Garçons became more than a fashion house — it became a movement of thought, a new vocabulary of emotion.

VIII. 2020s — Between Worlds

Even now, at the age when most retire into legacy, Rei Kawakubo continues to explore.

The 2020s have seen her engage with questions of technology, isolation, and transformation.

| Year | Collection | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | “Neo Future” | Humanity in digital exile |

| 2021 | Homme Plus “Metal Outlaw” | The romance of rebellion |

| 2023 | “Black Rose” | Beauty and resilience entwined |

| 2024 | “In-Between Worlds” | Duality — light, dark, visible, hidden |

Every season feels like a continuation of her lifelong dialogue:

What is the self when stripped of beauty?

What is form when stripped of function?

IX. The Language of Imperfection

Rei Kawakubo’s universe can be translated into four principles:

╭────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ DECONSTRUCTION → Break the illusion. │

│ ANDROGYNY → Dress the spirit, not gender. │

│ IMPERFECTION → Truth is never symmetrical.│

│ FREEDOM → Make without fear. │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────╯

She has no muse, no manifesto — only curiosity.

Every seam is a question, every wrinkle a word.

Fashion, in her hands, becomes a language of imperfections — where every flaw reveals the human beneath.

X. From Japan to France — The Dance of Two Worlds

The title of this story — “From Japan to France” — is not geography.

It is philosophy.

It is the journey of discipline meeting drama, of minimalism embracing excess.

From Tokyo’s restraint to Paris’s expression, Kawakubo built a bridge that others now walk across.

| Aspect | Japanese Spirit | French Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Subtle, meditative | Bold, emotional |

| Tone | Wabi-sabi (imperfection) | Haute couture (perfection) |

| Result | The paradox called Comme des Garçons |

This fusion redefined global fashion — not as East or West, but as something in between.

XI. The Woman Behind the Silence

Rei Kawakubo rarely speaks. She appears like a shadow — dressed in black, hair cut like punctuation.

When asked to explain her collections, she often shrugs.

“I don’t explain my work.”

Her silence is her power.

In an age of constant noise, she remains a whisper — and the world leans closer to listen.

Her husband, Adrian Joffe, manages the brand’s empire — Dover Street Markets across continents — yet it is Kawakubo’s quiet pulse that guides them all.

To this day, she works in the same Tokyo office, designing with scissors and instinct, not sketches.

Her empire hums not with algorithms, but intuition.

XII. The Legacy of the Unfinished

Fifty years later, Comme des Garçons remains undefinable — an idea that continues to move, evolve, question.

Rei Kawakubo taught us that fashion could be thought.

That rebellion could be silent.

That black could be light.

That beauty could be broken.

╔═════════════════════════════════════════════╗

║ “I never wanted to fit in. I wanted to ║

║ stand for something.” — Rei Kawakubo ║

╚═════════════════════════════════════════════╝

From Japan to France — and beyond both — her work has become the thread connecting art, emotion, and identity.

Not a brand. Not a trend.

But a mirror — reflecting everything that fashion could be when it dares to feel.

XIII. Epilogue — The Eternal In-Between

In the end, Comme des Garçons is not about clothes at all.

It is about freedom disguised as fabric.

A rebellion wrapped in silk.

A question posed in cotton.

Some designers build trends.

Rei Kawakubo built worlds.

Worlds where the ugly becomes sacred, where the broken becomes whole, where the in-between becomes home.

And so, the scissors still whisper in Tokyo.

The Paris lights still dim.

And somewhere between the two, the next revolution waits — quietly, beautifully, imperfectly.